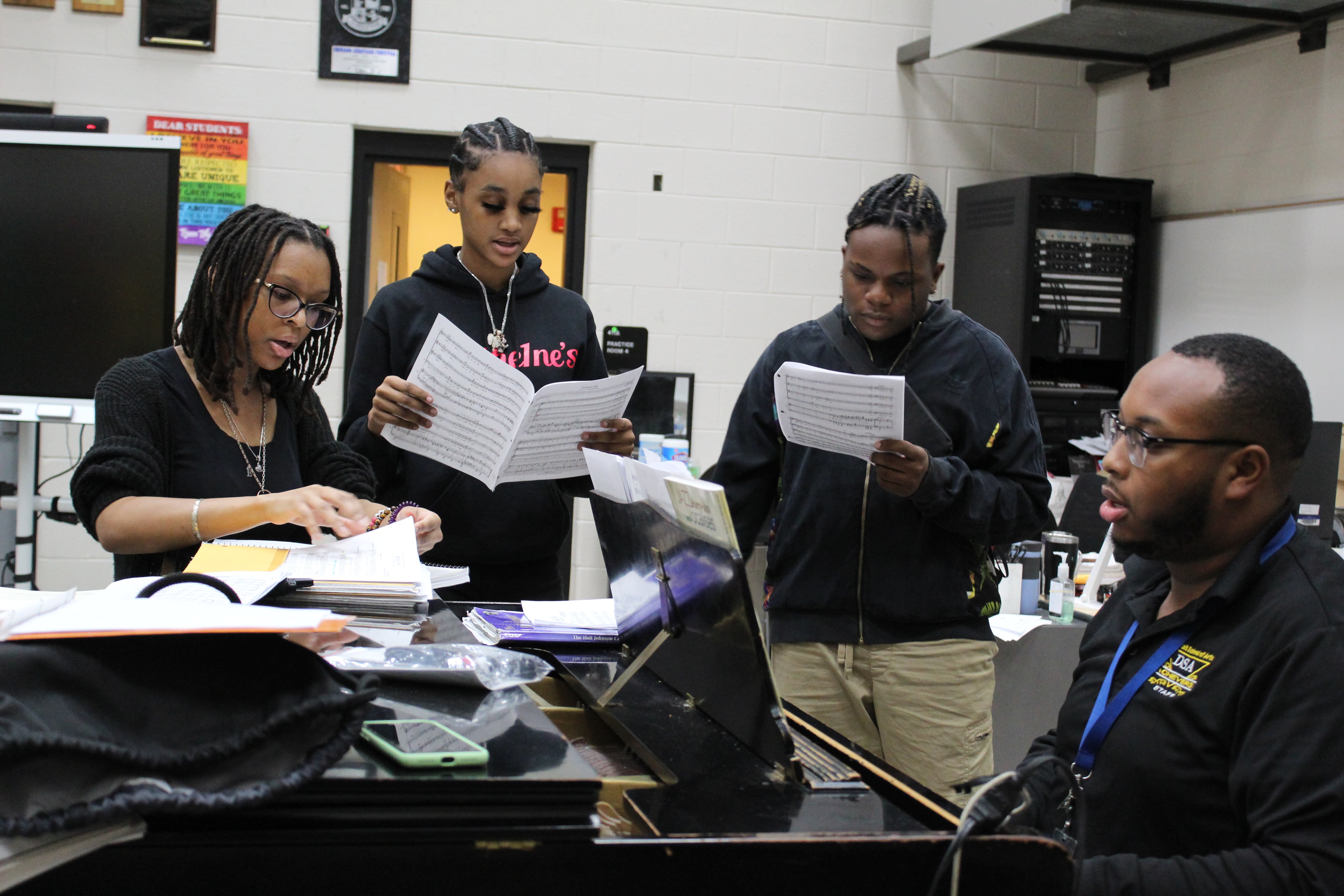

The three students started out singing softly, tiptoeing through the first few bars of a challenging jazz tune.

They stumbled over a syncopated rhythm, but didn’t lose focus. They listened carefully to their teacher’s coaching, and responded.

Soon, they were pulling off some of the tougher harmonies of “Sweet Georgia Brown.” When they hit just the right notes, the sound seemed to expand and fill the choir room at Detroit School of Arts.

It was the second week of classes at the high school, and learning was in full swing. And this was just lunch hour.

“I’m excited for the year,” said Ray Mich, a senior countertenor who joined the lunchtime practice.

Returning to the choir room “is like seeing your best friend who you haven’t seen in a long time,” added Justyce UpShaw, a senior soprano.

Rewind two years, and that kind of enthusiasm for school would be hard to find in Michigan. Students were logged in to virtual classrooms on computer screens. There were no live choir concerts and few opportunities to see friends. Education became a daily slog that took a toll on students’ attendance, test scores, and mental health.

The path back to engaged, joyful education may run through spaces like Julian Goods’ choir classroom at DSA, an application high school in the Detroit Public Schools Community District that is a centerpiece of the district’s efforts to expand its art offerings and its enrollment.

Students here take ownership of their learning: The trio who showed up to practice during lunch are senior members of the school’s Concert Choir — one of seven choirs at the school — who wanted to be able to help other students with the music. They are coached by Goods, an accomplished pianist and singer in his own right. And they’ll get a chance to show their learning in concerts and choral competitions.

Tackling real-world challenges

Already, the school year feels different for Goods.

“Last year, every teacher was a little burnt out at the end of the year. So I was a little anxious about doing it again,” he said. “But my kids have been an inspiration for me. There’s an excitement, a level of confidence.”

If only that type of excitement could be sustained across the curriculum, in math or science class.

In fact, it can, say education researchers Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine.

Just before the pandemic, Mehta and Fine opened a public debate over why so many teenagers in the U.S. were bored at school. They argued that core academic classrooms could learn some lessons from extracurriculars like choir, robotics club, or debate, where students tend to be more engaged. Rather than being told by a teacher how to build a robot and asked to reproduce that information on a test, students in these settings are asked to put their knowledge into practice in a consequential, real-world scenario like a robotics competition or a concert.

Such challenges tend to galvanize students’ interest in a topic, they said, and encourage them to learn the new skills they’ll need to succeed.

“There are a lot of transferable skills that come from places like choir that can be highly relevant to all kinds of situations,” Fine told Chalkbeat. “Yes, students are going to learn something about the song they’re singing, but more importantly they’re learning about how to put in careful work and attend to the parts that aren’t good yet.”

Fine said that this type of engaged learning does not need to be limited to magnet schools like DSA. Most high schools already offer a range of extracurricular activities, she notes, and core content teachers can inject excitement into their lessons by tying academic concepts into real-world projects that are relevant to students’ interests and communities.

In one school Fine and Mehta studied, students were asked to work on a carpentry project that required students to develop their physics and math skills.

“I just wish math class could have more of the qualities of choir, where we’re working together to produce something valuable,” she said.

The Detroit district aims to bring that spirit to neighborhood high schools across the city through “‘career academies,” where students can take courses in sports management and vet sciences, said Superintendent Nikolai Vitti. In core subject areas like literacy and math, teachers are being encouraged to boost student engagement by linking instruction with students’ cultural backgrounds.

“This looks like centering authentic student work and projects that lift up their voice, layering in many kinds of texts and media to lessons, and having more fun in the classroom,” Vitti said in an email.

Learning notes, building confidence

Goods’ walls are adorned with college pennants, trophies from choir competitions, and posters of jazz legends and civil rights activists — Lena Horne, Sarah Vaughn, Fannie Lou Hamer. Students did most of the decorating after he left the walls blank for a bit too long. “This is their room as much as mine,” he said.

The students who practiced “Sweet Georgia Brown” during lunch hour are among the strongest singers at Detroit School of Arts, an auditioned program whose alumni include singers Aaliyah and Teairra Marí.

They’re just starting to learn jazz harmonies for a class in Vocal Jazz, and the learning curve is steep, but Goods knows they will have the tune down pat within a few months. So he focuses on boosting their confidence, insisting that it’s better to make mistakes than to shy away from a difficult note.

Later on, Mich went quiet during a tough passage. “I’m scared of cracking,” he confessed.

“Nobody likes cracking,” Goods says. “If you don’t try, you’ll never get it.”

Later, when a soaring harmony fell apart, Goods looked quizzically at UpShaw.

“Are you scared of that high G?”

She stared back.

“Yes.”

“Try it again. One, two, three, four.”

The piano danced into action, and the students locked into their parts, sounding more confident after just 15 minutes of practice.

UpShaw nailed the high note.

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@chalkbeat.org.