Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free monthly newsletter How I Teach to get inspiration, news, and advice for — and from — educators.

As a first-year teacher in 2007, Eric Jenkins often sat in the dark next to a copy machine in a small shed in Ibadan, Nigeria, waiting for the power to come back on.

Rolling blackouts at the American school there were frequent, he recalled, which meant that it was a gamble to try and make all of your copies in one sitting.

“So much reflection and planning happened in those moments between the power shutting off and coming back on,” he said. “It forced me to focus on what I had available and in front of me at the present moment. It not only made me appreciate my life stateside but also helped me affirm that being an educator is the best way to impact the world.”

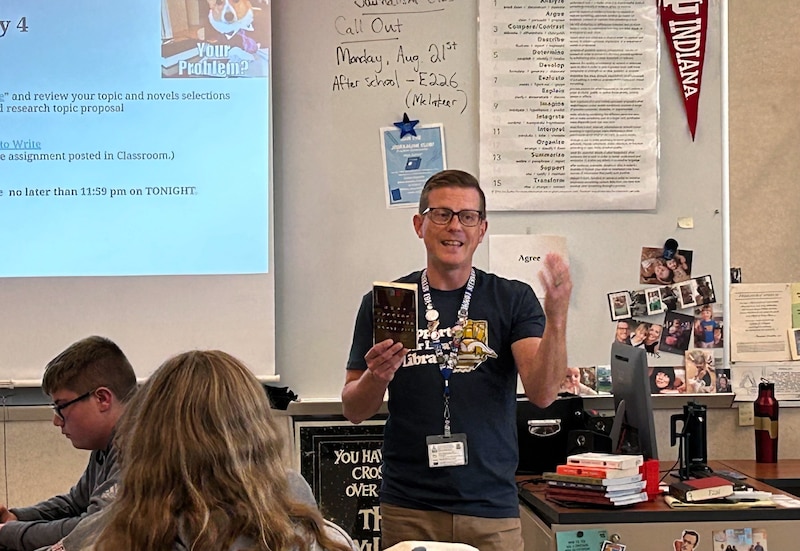

This year, Jenkins marks his 10th year at Franklin Community High School in Franklin, Indiana, with one of the state’s highest awards: the 2024 Indiana Teacher of the Year title.

His passion for travel prompted Jenkins to pursue his secondary education degree in English and language arts, with the idea of teaching English as a foreign language. During a study abroad trip in college, he met a French teacher who would later extend an invitation to him to teach in Africa.

Jenkins’ love of language continues to shine on the job: At Franklin Community High School, he teaches English language arts and a dual enrollment writing course offered through his alma mater, Indiana University.

“Both professionally and personally, the study of language arts, literacy, and composition has opened so many doors for me,” Jenkins said.

He is also a teacher consultant for the Hoosier Writing Project, which helps educators hone their writing skills and, in turn, become better writing teachers. Some of his best teaching strategies, he said, come from fellow teachers in the program.

After returning from Nigeria, Jenkins taught in Trussville, Alabama, before earning his master’s degree in literacy and moving back to Indiana. Jenkins recently spoke to Chalkbeat about teaching tips, life-altering interactions, and lessons learned from his travels.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What lessons did you take from your time teaching in Nigeria?

During that school year, I met so many wonderful people. My sixth-graders, in particular, taught me the power of sharing our backgrounds and experiences and the need to create a classroom community. Every day was a lesson in culture and connection — and food. The food was amazing.

The school was located in a walled compound outside of central Ibadan. You know the joke about teachers living at school? Well, we actually did. There was a house on the school grounds that we lived in, a short walk away from the classroom buildings. Three other American teachers and I shared that house. Describing it that way sounds like a pitch for a reality show, doesn’t it? In some ways, it was.

The teachers in that house really leaned on one another for support in so many ways. Thinking back on that now, I realize that it really shaped my views about the kinship among teachers. Regardless of content area or age range, there is an automatic bond and level of understanding among fellow educators.

Can you recall a memorable time, good or bad, when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach?

Recently, I have been thinking a lot about legacy in public education. But it was not until I had an impromptu meeting with parents two years ago, that I realized that legacy in education is generational, too.

Their student was starting his senior year, and our meeting marked the last “back to school night” for them as parents. Not only was there legacy in the fact that I had had that student in his sophomore year and now again as a senior, but they were also because he was the third and last sibling to be in my class. Their oldest was in my class during my first year at FCHS.

It dawned on me that a significant part of their experience with English language arts and writing had been shared with me over the course of nearly eight years. They had grown up with me, and I with them. And even though the parents and I had only spoken a few times in person or over email over the years, I felt a genuine sense of connection with their family. That moment broadened and deepened my understanding of the impact that teachers have on their communities. Teaching is so much more than a singular moment or an anecdote, it’s an impact that lasts for generations.

What part of your job is most difficult?

All meaningful work is difficult.

The constant battle with time is (and always has been) a difficult part of being an educator, but I would say the biggest challenge is being a parent and an educator at the same time. It’s a real test of stamina and patience.

However, being a parent has made a positive impact on my teaching as well. I feel more at ease communicating with parents. That first parent conference or phone call as a new, twenty-something teacher can be terrifying. But now, like with teachers, there is an automatic shorthand. There is a shared understanding of all of the joys and challenges that come with raising children.

Tell me about your favorite lesson to teach – where did that idea come from?

I am a firm believer that choice is the best way to engage someone. I try to look for ways to incorporate choice into any project. It’s a delicate balance, though.

For a long time, debates in my class fell flat. So, I decided to give students free rein on their topics. While the students chose topics that they were personally invested in, it did not go well. Students were too dug into their viewpoints and positions, which resulted in more division than productive discussion.

So I decided to change from having a traditional debate to preparing mock trial performances. The cases still provide choice, but the fictionalized scenarios offer the freedom for them to explore many different points of view. With debates, their personal views were put on display to be dismantled and judged by their peers. Mock trials offer a chance to role-play and pretend; it’s competitive, but there is not as much on the line for them personally. It’s an activity that has become a staple for my sophomores in the fall.

What’s the best advice you’ve received about teaching?

I have been fortunate to have so many brushes with greatness.

One that I have been thinking about a lot lately is Simona Herring, my mentor teacher in my first year at Trussville. Simona is the embodiment of Maya Angelou’s lines, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

She helped me understand that we are in the business of teaching people, not content. We hope that students take away lessons about reading, writing, and speaking, but even more importantly, we want students to leave feeling seen, heard, and appreciated.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Lawrence Township schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.