Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

Could more remote work keep teachers from leaving the field?

If a school can’t find a calculus teacher, could it share with another school down the street?

And, most importantly, why are teachers quitting the profession?

These are the kinds of questions that a new project at Lawrence schools hopes to answer in search of solutions to common “pain points” in education that are driving down teacher retention rates.

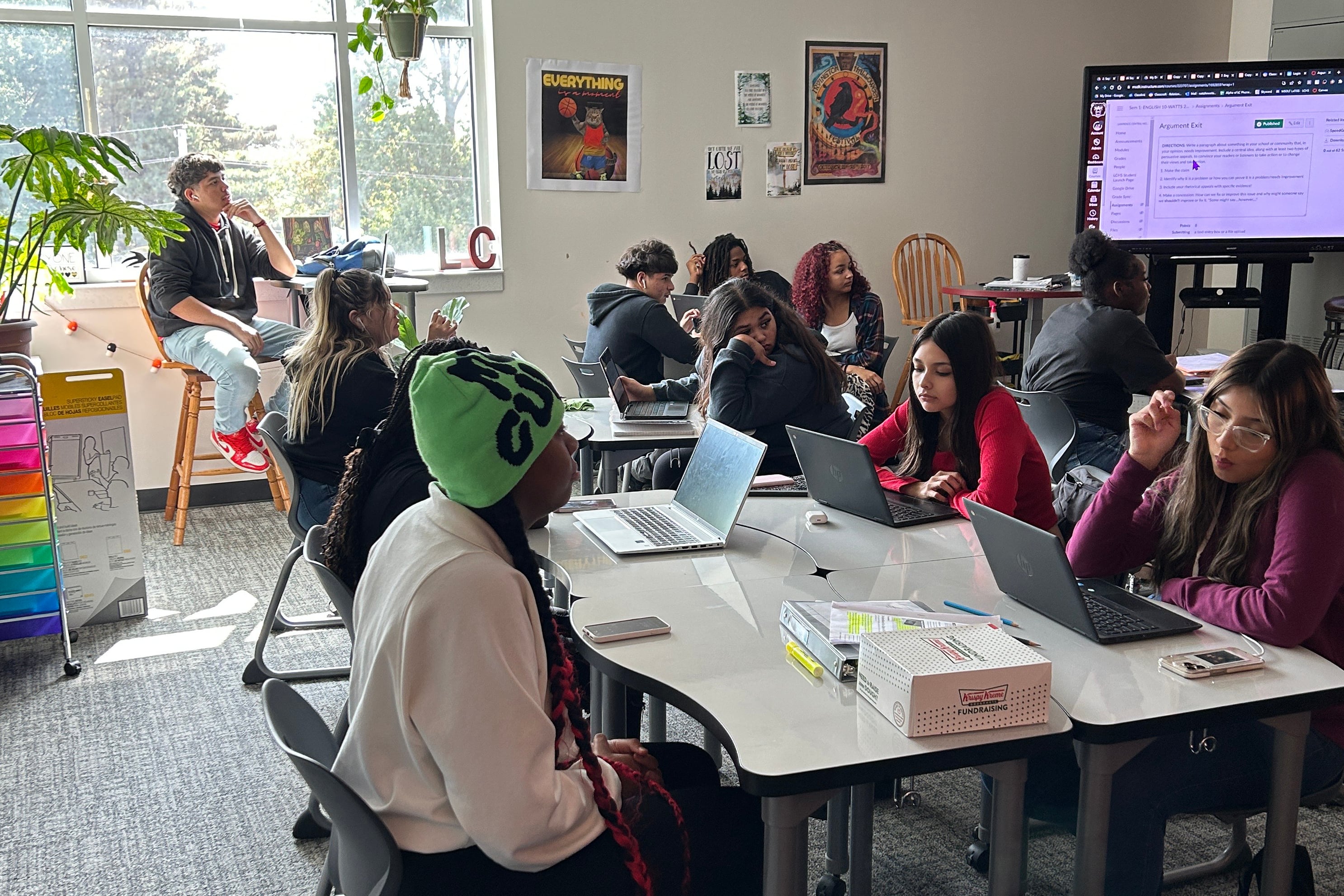

Fifteen teachers and administrators, representing each of the district’s four middle and high schools, are participating in the Reimagining the Teacher Role Cohort led by Teach Indy, an Indianapolis-based nonprofit. Cohort members are interviewing their colleagues, identifying issues, and finding solutions to pilot at each school next year.

What these will be is still to be determined, said Sara Marshall, executive director of Teach Indy, but could include proposals to give teachers some of the benefits of remote work, or fill vacant positions in creative ways.

The goal is to raise teacher retention rates that dropped in the wake of the pandemic and have yet to recover. Data from the Indiana Department of Education compiled by the Fairbanks Foundation indicates that statewide teacher retention rates dropped from 84% in 2021 to 77% in 2022, before recovering slightly in 2023 to 80%.

In Marion County, that rate dropped from 70% in 2021 to 66% in 2022, also recovering slightly to 68.5% in 2023.

And, in Lawrence schools, teacher retention dropped from a high of 86% in 2021 to around 77% in 2022 and 76% in 2023.

There are a number of reasons why teachers typically leave the profession, Marshall said, including workload, pay, and a lack of respect. Fewer candidates are entering the profession to replace retirees, she added, and some teachers have left to pursue remote positions.

The project allows teachers from the four schools to brainstorm together on how to reverse these trends, but the solutions they’ll put in place might be unique to each building, said Andrew Harsha, the district’s director of secondary learning. The district doesn’t have money committed to the solutions, but may rely on fundraising or grant funding in the future, according to a representative of Teach Indy.

“We are leaning on our teachers to help come up with solutions, leaning into them for innovation and creativity,” Harsha said.

One of the cohort’s possible solutions could be some flexibility in the workweek, giving teachers a four-day teaching schedule, with the fifth day allotted for remote work or professional development, Marshall said.

The fifth day for students might be supervised by substitutes or community organizations, she said. A similar idea was considered at Indianapolis Public Schools in 2022.

Another solution might be to share hard-to-fill positions, like math and science teachers, between schools, Marshall said.

“I think schools are going to have to think creatively,” Marshall said.

The project, which launched in January, began with teacher teams interviewing their colleagues about their experiences — both positive and negative. Their questions seek to find out what teachers like about teaching, as well as whether they’d ever considered leaving the profession, and if they could pinpoint what might alleviate their stress.

One of the common themes so far is that working with students is a source of joy for teachers, said Rachel Anderson, a Lawrence Central High School math teacher who’s part of the project.

“It’s what gives people energy and makes them feel positive. But sometimes that’s the thing making them more tired, too,” Anderson said.

Anderson said her team’s goal is to interview teachers from a wide range of backgrounds — including those who took nontraditional paths to teaching — in order to learn more about what’s important to them.

As a teacher who took an alternate route to licensure through the state’s Transition to Teaching program, Anderson said she values mentorship, which helped her find her footing as she started teaching. But ultimately, any solutions the cohort comes up with will be informed by her colleagues’ thoughts.

“I have some hopes of what I want, but I know that no program that we implement will be successful without that input,” she said. “This is work we’re trying to do with people, not to people.”

The Lawrence project intends to roll out building-level pilot programs next school year. Teach Indy hopes to work with more districts on future projects.

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.