Sign up for Chalkbeat Newark’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

In November, a 15-year-old Central High School student was shot during a drive-by after students were forced to evacuate the Newark school due to reports of a gas leak. In March, two students were shot outside West Side High School as students were being dismissed.

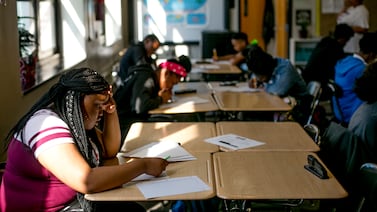

As city leaders aim to prevent other incidents like those and keep teens off the streets, Newark this Friday will start to enforce a youth curfew that has long been on the books but never enforced.

The curfew for teens under 18 is in response to an uptick in youth engaged in violence or victims of it, “mostly in places where teens shouldn’t be after hours,” Mayor Ras Baraka said at a press conference last week.

But Nora’a Armstrong Johnson, a senior at Essex County Payne Technology High School, can foresee resistance to the new curfew among her peers and says she isn’t sure if it will help cut back on youth violence. The Newark youth curfew will be in effect Friday through Sunday beginning on May 3. On June 21, when the school year ends, the curfew will be enforced seven days a week between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m. as part of the city’s Summer Safety Initiative, which also includes summer programming, Baraka said.

Newark police who see teens without an adult during curfew hours will stop them and request their home address and information before contacting the city’s Office of Violence Prevention and Trauma Recovery, which will take teens to their homes.

If a parent or guardian is not at home or can’t be reached, teens will be taken to the city’s new reengagement center, which will stay open until 2 a.m. during the curfew, city leaders said. If parents are still not reached, teens will be transported to a local hospital to receive a medical clearance and, if they are not picked up by a parent or guardian after four hours, the New Jersey Division of Child Protection and Permanency will be contacted.

Baraka says the curfew is not “a police event” and there are no fines or penalties for teens who break it. The rule is meant to engage city teens who may not usually seek help, Baraka added, such as youth who are not in school or working, who make up 1 in 5 Newark teens and adults 16 to 24.

“What we’re doing is trying to take people home,” Baraka said. “There actually may be kids that we find on the street who have run away or kids who are dealing with issues at their home who may not want to be home.”

National report shows youth crimes peak after school

More than 400 towns, cities, and counties have enacted youth curfew laws, according to the National Youth Rights Association. But youth “crime reduction efforts should focus on the after school and early evening hours,” according to the 2022 Youth and the Juvenile Justice System report by the National Center for Juvenile Justice. Violent crimes committed by youth peaked after school at 3 p.m. and “then generally declined hour by hour until the low point at 5 a.m.,” according to the report.

The report found that 64% of all violent crimes by youth occurred on school days, and nearly 1 of every 5 of these crimes, or 18%, occurred between 3 p.m. and 7 p.m. During standard curfew hours, 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., 14% of violent crimes were committed by youth, according to the report.

Across the country, violent crimes against young people doubled in 2022, according to the FBI’s National Crime Victimization Survey data as youth arrests for those crimes, which include murder, robbery, and aggravated assault, have been on the decline. In public schools across the nation, 67% reported having at least one violent incident during the 2021-22 school year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Johari Sutton says she began hearing about fights among her peers starting in eighth grade.

The now-12th grader attended Phillips Academy Charter School in middle school before moving to Englewood with her family at the start of high school. Although she was never a part of those fights, she would often hear about them at school or from students like her cousin, who attended Central High School and saw fights often, Sutton said.

She feels that violence among her peers often stems from encounters outside of school and on social media before turning into physical altercations. The role models around them also play a part, Sutton said.

“They’ll see like adults fighting and then they’ll think that that’s how they’re supposed to solve their problems and they’ll bring that to school,” Sutton said. “So if someone like roasts their hair on Instagram or something, they’ll be like, do you want to fight or something?”

In Newark, groups like Hear My Cries are working to reduce violence in the city. They partner with city and local leaders in hosting after-school programs for Newark teens and most recently, organized a peace walk in the city’s South Ward to raise awareness about violence among young people.

Sean Kirby was among those walking down Clinton Avenue last Thursday chanting “stop the violence” and holding signs that read “peace” as residents driving by honked in support of the marchers. Kirby, a Hear My Cries volunteer who helps run the organization’s after-school program on Bergen Street, said he thinks the youth curfew won’t work because some teens like to hang out outside their homes where, he believes, drug-dealing happens.

“I know because I used to do that,” said Kirby, who in previous years found himself in and out of prison due to drug-related charges and other offenses

Armstrong Johnson, who turned 18 in April, won’t be affected by the curfew but thinks following it could pose problems for some teens. Johnson remembers instances where she was out late with friends who didn’t want to go home and fell into arguments with them.

Although she’s never seen or experienced a violent crime and thinks her Central Ward neighborhood is not dangerous, she doesn’t think it’s safe enough to hang out with friends at night. She’s also heard of fights outside her school and others in Newark as well as shootings involving teens.

Even though Armstrong Johnson wonders if her peers will follow the curfew, she believes Newark residents should also enforce it. For instance, she said, if someone is hosting an event that will go past curfew, they should check the ages of guests.

“Are they actually over 18? If they’re not, send them home,” Armstrong Johnson said.

Jessie Gómez is a reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city. Contact Jessie at jgomez@chalkbeat.org.