New York state officials will increase the number of hours students with medical conditions must receive after a flurry of questions from parents and school districts — but the mandate won’t take effect until the 2023-2024 school year.

The changes affect students who, for medical reasons, won’t be in school for at least 10 days over a three-month period and are learning from home or a hospital setting. Starting in 2023, these students must receive at least 10 hours of weekly instruction, up from five, if they’re in elementary or middle school, and at least 15 hours for high schoolers, an increase from 10 hours a week.

The increase does not go into effect until 2023 because state officials wanted to give districts time to budget properly, according to a spokesperson for the state education department.

“I think there was a common understanding that the five to 10 hours were not nearly enough,” Mary Beth Casey, assistant commissioner at the state education department, told the Board of Regents Monday.

State officials say the new regulations come after hearing many questions from caregivers and districts as the pandemic wore on about how to provide instruction for medically fragile children, including immunocompromised students. They’re also, for the first time, requiring districts to follow a timeline to approve and provide such instruction for these students.

In New York City, 20 different conditions qualify children for medically necessary instruction. This school year, just over 2,500 students applied for such services, and 84% of them were approved, according to an education department spokesperson, who did not immediately share the equivalent pre-pandemic data. Sixty-five percent of these children received in-person instruction, which involves a teacher coming to their home or another setting to teach them, while the rest was virtual.

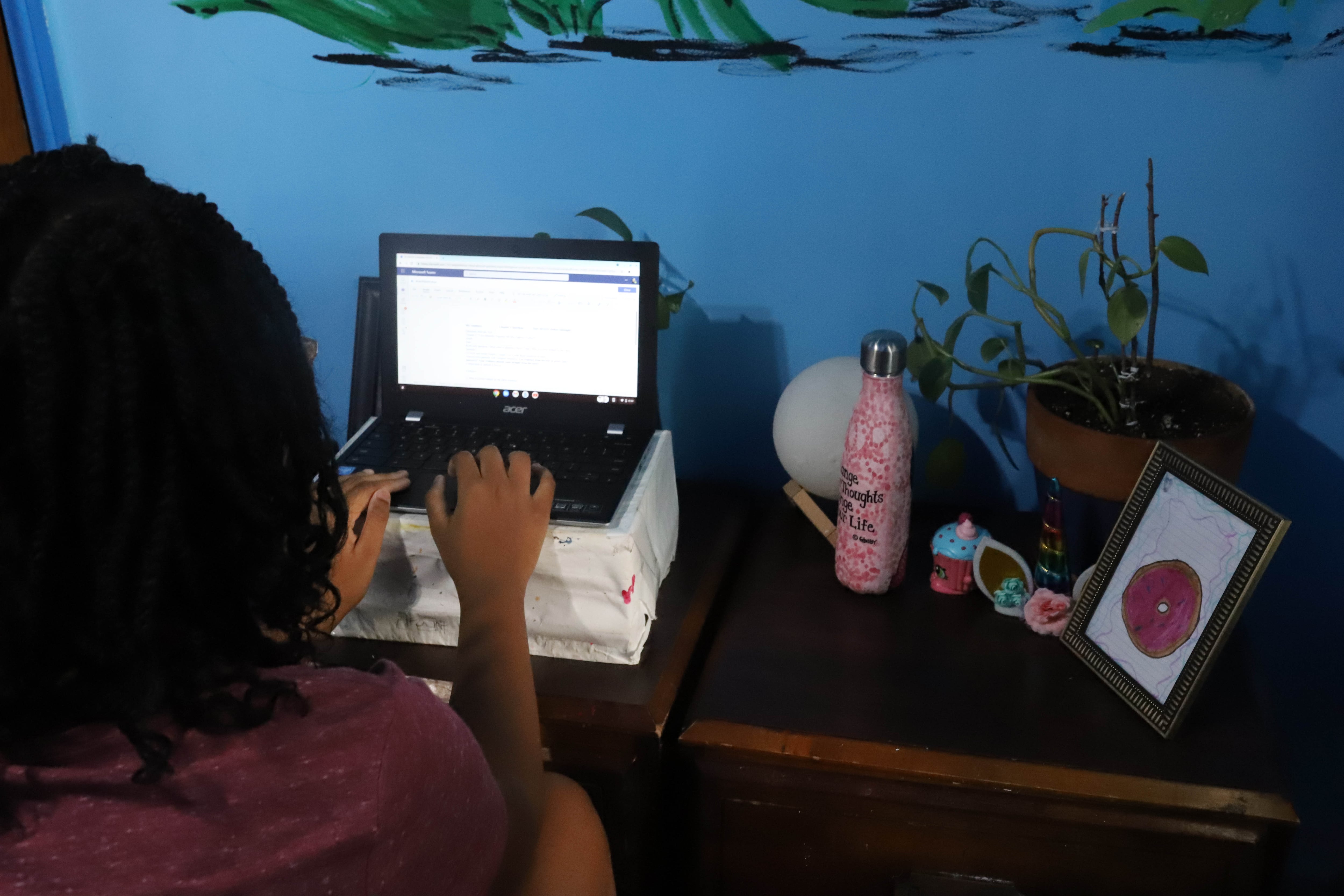

At the start of this school year, parents whose children have medical conditions and were at higher risk for severe COVID infections faced agonizing decisions about whether to send them back to school buildings. Should they risk their child getting infected, or should they apply for the home instruction program, which would mean getting 1-2 hours of schooling a day?

“We had to make a really difficult decision to send her to school,” parent Rodney Lee told Chalkbeat in October about his daughter who has a seizure disorder and was at a higher risk for severe COVID. “Every day we pray, and we hope that she stays healthy.”

The new rules will mean just an extra hour of learning a day for these students. Still, it’s a “really critical” change for families, said Maggie Moroff, a special education policy expert at Advocates for Children, who said that even pre-pandemic students at home were getting far fewer hours of instruction when compared to their peers in school.

“There was so little oversight, and experiences were so dramatically different, but in a world where more and more students are needing to learn from home in order to remain healthy and safe, we really want to make sure that they get the supports that they need,” Moroff said.

The state also created several more requirements that districts must meet.

Previously, there was no required timeline around how quickly students could be approved and receive such instruction. Starting this July, districts must start home or hospital instruction for a child within five school days of either being notified of that student’s medical condition or a guardian’s request for such instruction — whichever happens first. Districts must decide and notify parents whether their child is eligible for home or hospital instruction five days after a parent or guardian sends a doctor’s note verifying the child’s medical condition. Parents can appeal a denial within five days, but the district must continue providing services while the appeal is being considered.

Creating an approval timeline could also have a big impact on families. Moroff said some cases took so long for services to be set up, that some children lost months of schooling.

“We would wait sometimes for months for their home instruction to start, even after it had been approved,” Moroff said.

The state is also requiring districts to create plans for these students that describe how many hours of instruction they’ll receive and how their lesson plans are keeping them on track — something New York City already does, the city spokesperson said.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.