Denver teacher Vanessa Lugo-Acevedo was recently honored by the White House. The daughter of immigrants, she describes why a child’s cultural background must be viewed as an asset.

There are no words to adequately express how deeply honored I am to be receiving the Champions of Change award. As a Hispanic female, a child of immigrants and an English language learner, I feel that my entire life I have been preparing to engage in this work in our community.

Upon graduating from UCLA in 2010, I entered the profession of teaching through Teach for America, an alternative licensure program founded by Wendy Kopp, whose mission is to place high-achieving college graduates as teachers in our highest-need schools. I was placed as a bilingual educator, meaning I could be hired as anything from a pre-K teacher to a high school Spanish teacher.

I will never forget my first and only teaching interview with the staff at Cole Arts and Science Academy in Denver. It lasted for about 15 minutes over Skype. It was the last question and my answer to that question that changed my life: Why should we hire you over anyone else?

My response: I see myself reflected in the students that I will be teaching. I grew up in a low-income neighborhood and I received free lunch at school. My parents are immigrants from Mexico and when I began school, they did not speak English and neither did I. I want to demonstrate to my students and families that there are no limits to what they can accomplish.

Querer es poder. Where there is a will, there is a way.

Reflecting my students racially, culturally and linguistically

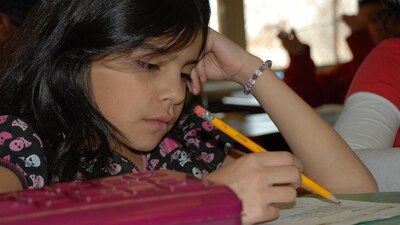

In my classroom, grassroots transformational change has revolved around the idea that a student’s background and culture should be an asset. It should never be considered a barrier to success. This mindset has illuminated my path in education both in and outside of the classroom.

In my practice as a bilingual educator, my belief is carried out in viewing and using my students’ and families’ native language as a sacred tool to learn English and in English. It has helped increase student engagement in my classroom by ensuring that the lessons I teach my students are reflective of who they are racially, culturally and linguistically.

As a first-year teacher, this began as simply making sure the classroom environment was representative of the students in our classroom as well as being intentional about the texts that I selected for our read aloud, making sure that they reflected my student’s cultures and their interests.

When I saw how much more my students enjoyed the books that had characters that looked like them, I was motivated to make my curriculum student-centered. I began to design more learning experiences that affirmed the diversity within our classroom incorporating students’ native language, musical interests as well as favorite foods.

In order for students to value and see their background and culture as an asset, we as educators MUST see our students’ cultures and backgrounds as assets.

The tragic effects of sympathy and excuses

Culture and background can only be seen as an asset when, as a nation, we cease to look at our students and families of color from a deficit perspective. I have seen firsthand the tragic effects of sympathy and excuses for why students cannot learn. I believe that this is part of the problem in our education system today.

Sympathy and excuses must stop.

As a nation, we must come to terms with the fact that our kids and families do not need our sympathy. Let us vow to take an asset-based perspective, seeing our students and families for who they are: strong, intelligent, and capable human beings with rich, vast, and varied life experiences.

In my time as an educator and my lifetime as a student, I have found that the key to success in school lies in building solid, positive relationships with students, families, caretakers and the community at large and maintaining high expectations for all regardless of circumstance.

Our students and families need to know that we love them too much to let them fail, the future of our nation depends on this. To do this, we must know who our students are and what their hopes and dreams are – because if we cannot motivate them and inspire them, how do we expect to teach them?

More than a mouthpiece for the powerless

Outside of the classroom, my work in education has revolved around systemic transformational change in the realm of teacher education and support.

As a Teach for America corps member, I felt that the program’s programming around diversity, community and achievement left much to be desired especially since the students we were about to teach were children of color. As a result, I have spent the past two years working with Teach for America to increase corps members understanding of our students of color and our English language learners.

This past summer I worked as a corps member advisor, partnering with 12 promising new teachers from Hawaii, Ohio, Indianapolis, Colorado, New Mexico and Phoenix to support them in developing the skills they will need to feel prepared to enter their classroom this fall.

Additionally, I worked closely with an amazing team of our 14 staff members charged with the task of facilitating a series of sessions on diversity, community and achievement. The sessions explored topics of race, class, and real and perceived lines of differences, all topics that are pertinent to both new and current teachers in the landscape of our public schools.

In my work, my goal is to be more than a mouthpiece for those who often feel powerless. My goal is to empower them so that they feel the confidence and exuberance to share their stories, their hopes and their dreams.

This blog is cross-posted from the White House’s Champions of Change website. For more stories by educators, visit the site.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.