Equity may be a buzzword in education, but state test scores released this year underscored why so many Colorado educators are focused on closing academic gaps between less privileged students and their more privileged peers.

In Denver, the gap between the percentages of white and Hispanic students scoring at grade-level on state literacy and math tests was as big as 50 percentage points in some grades, according to test score data released this fall by the Colorado Department of Education. All 10 of the state’s largest school districts had achievement gaps based on race.

The gaps between poor and wealthier students in most of the large districts were also wide. They were smaller in Aurora — not necessarily because the suburban district’s poor students did much better on the tests, but because its more affluent students didn’t do as well.

The data also showed significant gaps between students with disabilities and those without. In Jeffco, for example, just 7 percent of fourth graders who receive special education services scored on-grade level in math, compared to 43 percent of fourth graders who do not receive services.

It’s more difficult to tell from state test results how students learning English as a second language are doing because of the way the state groups them.

Districts and schools across the state continued this year to try to squeeze shut those gaps through strategies like giving second language learners enrollment priority at popular schools.

Denver Public Schools, which has among the biggest gaps in Colorado, made several changes. Among them was the decision to dole out extra money to schools educating students facing particularly difficult challenges, such as homelessness or living in foster care.

The district also eliminated an advanced kindergarten program that served disproportionate numbers of white and affluent students, and rolled out a new online tool to help families evaluate schools. Unlike a previous version, the new tool can easily be used on a smartphone.

And more changes are coming: The district received recommendations this year from a community task force on how to better educate black children and attract and retain black teachers, and has already begun acting upon some of them. It received a different set of recommendations on how to increase school integration from another community committee.

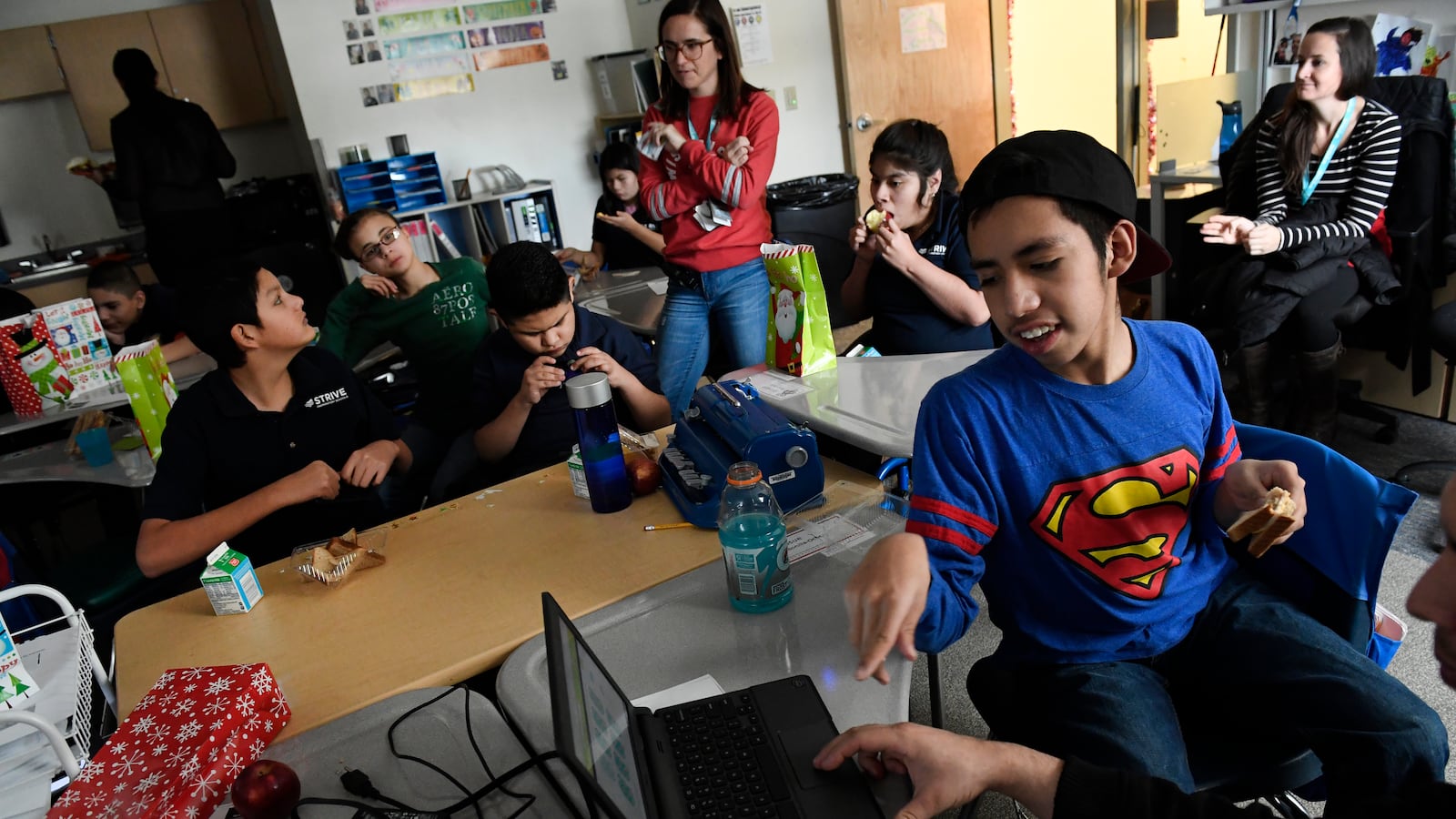

Charter school networks also tackled the issue. STRIVE Prep, a network of 11 elementary, middle and high schools in Denver, has an “equity agenda” that includes changes to enrollment and school practices with the aim of serving more high-needs students.

But challenges remain. In Denver, the inability of the district to fund transportation for all students continued to be a barrier to its vision of universal school choice. And while Denver Public Schools tried to provide black and Hispanic students greater access to its magnet programs for highly gifted students, they continue to be under-represented.

Statewide, teacher effectiveness data showed schools with the highest concentrations of black and Hispanic students had fewer teachers and principals rated effective or higher than schools with the smallest populations of students of color.

And although state lawmakers passed a bill setting a path for districts to offer “seals of biliteracy” to students who demonstrate fluency in English and another language, Colorado educators who led the way in developing the seals worried the new law sets the bar too low.