Mayor Bill de Blasio is widely expected to wind down his signature program for struggling schools. But before he does, city officials are planning to close a handful of turnaround schools, decisions that will be announced publicly in January.

The city has closed 14 Renewal schools since the program launched in 2014 with 94 schools. Now, the education department is poised to close more, according to a senior department official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Decisions about which schools will be on the chopping block have not yet been formally made, the official said. But the education department is planning to close fewer than last year, the largest single round of Renewal closures to date, when seven schools were ultimately shuttered.

It’s not entirely surprising that the department is eyeing additional closures. Though de Blasio has said they are a “last resort,” the city began closing some of the 94 original Renewal schools within a year of the program’s launch.

The closure decisions again throw the $750 million turnaround program into the spotlight, underscoring that despite a raft of extra social services and academic support, the extra resources have largely not lived up to the mayor’s promise of “fast and intense” improvements.

The looming closures also raise questions about the future of school turnaround in New York City. De Blasio has said the program, which is in its fourth year of what was initially described as a three-year effort, is reaching its “natural conclusion,” and that decisions about the 50 remaining Renewal schools will be made by the end of this school year. Yet city officials have declined to explain what will happen to schools that will avoid closure and have not made enough progress to leave the program.

“There’s a great deal of uncertainty about what their futures are,” said Aaron Pallas, a professor at Teachers College who has studied the turnaround program. “The chancellor hasn’t said much of anything that is suggestive of a comprehensive strategy of dealing with the remaining Renewal schools in particular, or struggling schools in general.”

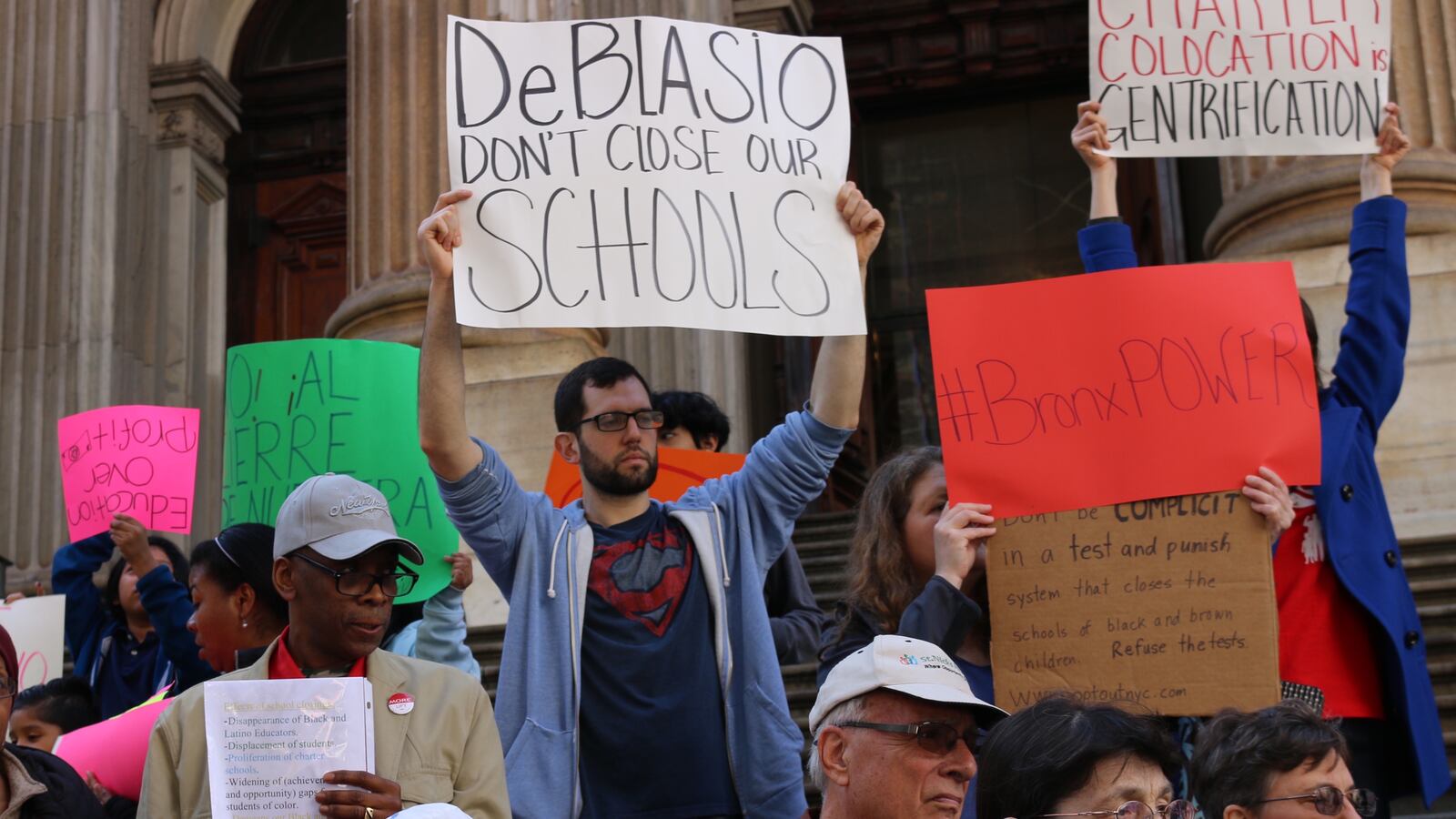

When the Renewal initiative launched, city officials framed it as the antithesis of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s approach, which involved closing over 150 schools and replacing them with new — often smaller — ones. Research has found that strategy showed some promise. But it also drew fierce protest from teachers, union officials, and disrupted long-standing neighborhood institutions. A number of the new schools continued to struggle, however, and would eventually become Renewal schools.

By contrast, de Blasio sought to keep schools open whenever possible. The city instead gave low-performing schools additional funding, access to non-profit organizations that would help provide physical and mental health services, and academic resources, such as additional teacher training and leadership coaches.

Research on de Blasio’s approach shows its effect on school improvement has been mixed at best. And the New York Times recently reported that city officials initially predicted that about a third of schools in the program would never make significant strides.

Of the 94 original schools, 14 have been closed, nine have left the program after being merged with other schools, and city officials said 21 have shown enough progress to slowly ease out of Renewal. No schools have been added to the program since it began.

An education department spokeswoman did not respond to specific questions about the program and the city’s future plans for struggling schools, including how closure decisions will be made. In the past, officials said they consider a range of factors, including schools’ academic performance, feedback from families, staff turnover, and previous improvement efforts.

Increases in graduation rates and test scores have not been enough to spare some schools from being shuttered — and the city has even closed schools that have met a majority of their goals.

“We believe in investing in our schools,” education department spokeswoman Danielle Filson said in a statement. “We will share an update on the Renewal program by the end of the school year.”

Many Renewal schools still post test scores and graduation rates that are far below average, which could invite extra scrutiny. At Herbert H. Lehman High School in the Bronx, 57 percent of students graduate on time — roughly 20 points below the city average. At I.S. 117, 8 percent of students passed state math tests last year, and 16 percent were proficient in reading — an increase from 2015 when just 5 percent of students were proficient in either subject, though still far below average.

If Renewal schools performing below expectations avoid closure, it’s unclear how the city will continue to intervene to improve them. City officials have said Renewal schools will not lose the extra funding they received, or their “community school” designations, which are a core element of the Renewal program and allow schools to partner with nonprofit organizations and offer a range of social services, including mental health counseling and dental clinics.

Some observers said it’s possible the city won’t replace Renewal with another distinct turnaround program, especially since it has created headaches for de Blasio, and instead opt for a squishier system of support for struggling schools.

“That would be the politically wise way to go,” said Robin Veentstra-VanderWeele, the chief program officer at Partnership with Children, which serves as the nonprofit partner in eight city turnaround schools. “If you don’t tell anyone what the target is they don’t know what to shoot.”