Early on a Monday morning last November, I asked one of my most promising students, whom I’ll call Sean, how he ended up in my classroom.

I teach in District 79, which serves students who often require several layers of additional academic support. This student, having spent two years in one of New York City’s best public high schools, seemed out of place.

Sean sounded frustrated and upset in his response. “I was suspended for a whole year, so I stopped going to school,” he said.

Conversations like this have shown me the true impact of long-term suspensions. Rather than fixing or addressing difficult situations, suspensions harm students’ academic prospects and emotional well-being, and they are often meted out to the very students who need the most stability and care.

The majority of students at my District 79 school are students of color from low-income backgrounds. Many face obstacles to academic progress, including incarceration, unstable family and housing situations, or court involvement. A significant number are English Language Learners, have learning disabilities, or struggle with social and emotional stability, and many live with several of these factors.

Something else my students have in common is their history of receiving long-term suspensions. Seventy percent of the students in my first two periods last year had received suspensions ranging from 10 to 180 school days. Many report having received several, sometimes in the same school year, often as early as middle school. And with the exception of only one of these students, the events surrounding their suspensions happened during — and often because of — extreme personal or family trauma, as in the case of Sean.

One fallacy maintained by even the most well-intentioned people is that the kinds of students who end up in educational settings like mine do not care about their education. This is simply not true — students recognize and are upset by the ways long-term suspensions negatively impact their learning.

In the words of one of my students, “Once you’re suspended, you’re like a criminal in their minds. By the time the four months was up and I went back to school, I tried catching up to where every other student was, but I couldn’t, because I felt like no teacher liked me and no one tried helping me catch up … Not only that, but the Regents exams were right around the corner, probably a week or two away from when I got back, so I wasn’t even ready to take them.”

In conversations with my students, one after another has lamented the effect of their suspensions on their ability to do well in school, graduate with their peers, and move on to college or vocational training. For one, a capable scholar who was suspended for nearly an entire school year, his time in the suspension center caused him to fall too far behind his peers to catch up. For others, multiple shorter suspensions combined with learning disabilities had the same effect.

Because the suspension centers receive students from many different schools, the curriculum there, though taught by competent and caring teachers, does not necessarily correspond to the coursework in students’ regular schools. When students return to their home classrooms, even if they have done well while in suspension, they usually find themselves unprepared to pick up where they left off. And this is to say nothing of the added difficulties that a disjointed, unstable learning environment has on children who are already struggling with serious social and emotional issues.

Long-term suspensions also damage students in less obvious — but no less consequential — ways. Sean, like so many of my students, has internalized the message that the public school system “doesn’t care about students like me.” Others, especially students who struggle with English or who have learning disabilities, blame themselves for their schools’ shortcomings and describe themselves as “stupid,” “dumb,” or “bad.”

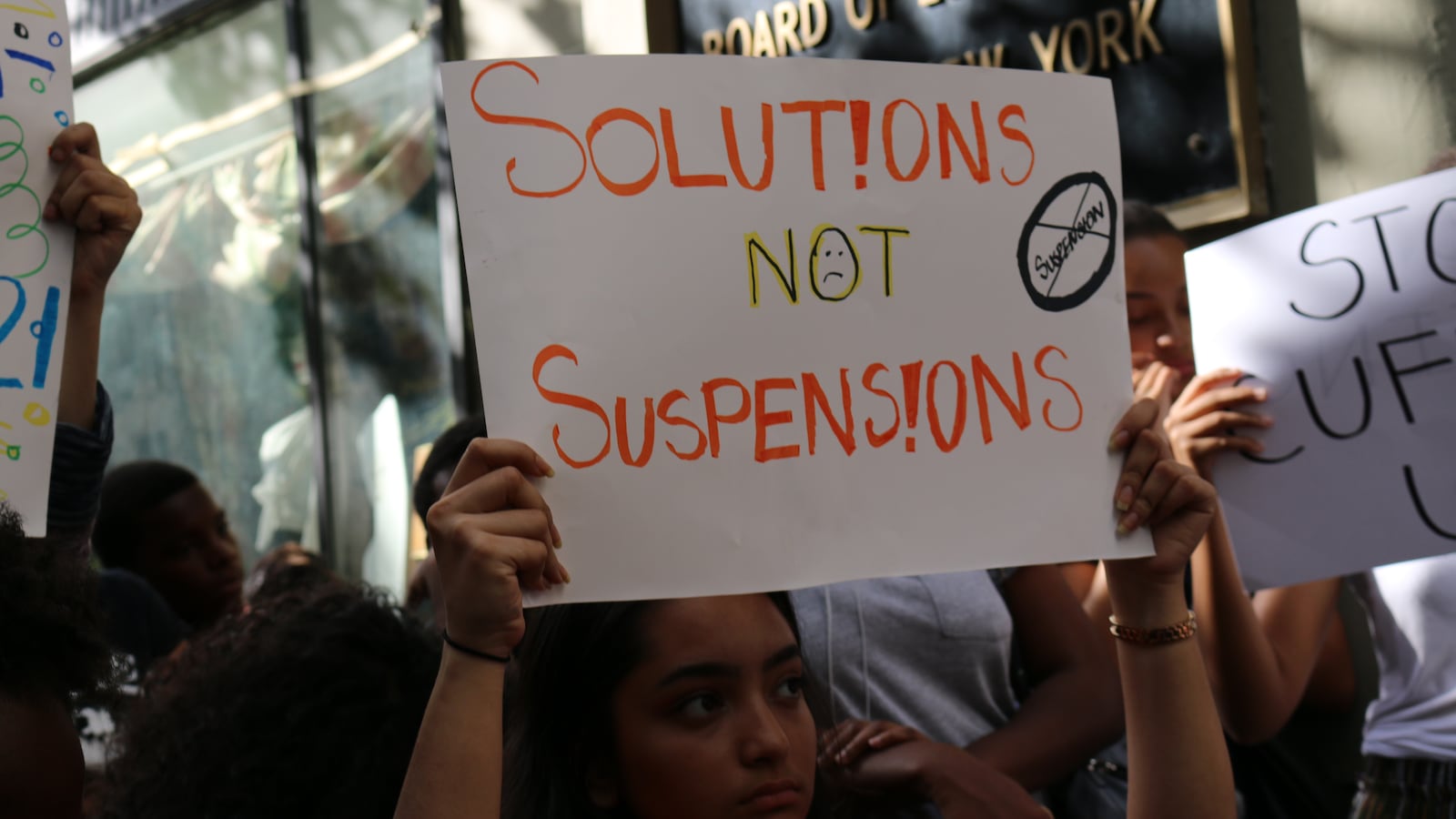

Partly because of my experiences as a teacher in a District 79 school, I got involved with Organizing For Equity New York. Together with Dignity In Schools New York, Teens Take Charge, and other local organizations, OFENY has jointly pushed for successful changes to New York City’s school discipline code: most suspensions have been capped at 20 days and 200 social workers will be added to city schools. The Urban Youth Collaborative worked tirelessly to ensure that the city will limit arrests and summonses that happen at school.

And while these are certainly steps in the right direction, they do not go nearly far enough. Even with these changes, there will still be more security officers than counselors in New York City schools. Metal detectors and other prison-like protocols will still greet many of our students, especially students of color, every morning when they get to school. Teachers and administrators will still be allowed to use suspensions to punish students in kindergarten, first, and second grade. Far too many students will still lack access to the supportive care and guidance every student should expect to find at school.

And — perhaps most importantly — school and district officials will retain the right to impose lengthy suspensions for cases they deem serious enough, leaving the door open to further abuses of the suspension policy that, given the city’s track record on race and school discipline, will likely affect low-income students and students of color disproportionately.

As the new school year and all of its promises approach, I’m thankful that students like mine will spend more time in the classroom. But we still have a long way to go.

Eduardo Lerro is a New York City public school teacher and a volunteer with Organizing For Equity, New York.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.